When Jon Rahm signed with LIV Golf for an estimated half a billion dollars last December, he made the smart play. Rahm became the second highest-paid athlete in the world (behind soccer’s Cristiano Ronaldo) with enough money to take care of future generations of his growing family. It also appeared as if he would soon regain the opportunity he had sacrificed by defecting to LIV—regularly competing against the best fields in golf.

Rahm’s soulful drive to be the best is what had made the 29-year-old Spaniard a commanding and compelling figure. However, smart alone can be soulless, which is why the move rang off key. Rahm had built his reputation on the historical continuum provided by the PGA Tour, to which he had emphatically declared fealty. He had rhetorically asked, “Would our lifestyle change if we got $400 million?” and immediately answered, “No.” When he reversed field with his announcement—while wearing a LIV letter jacket—it caused a whiplash from which the golf world still reels.

NEW YEAR, NEW ROLE Jon Rahm began his tenure as captain of LIV Golf's Legion XIII team in February at Mayakoba. (Top photo credit: Matthew Harris/Getty Images)

Manuel Velasquez

By putting money ahead of what had always felt like an uncompromising pursuit of greatness, Rahm, at a decisive moment for the professional game, had done what the modern giants—Palmer, Nicklaus, Woods—had declined to do. The thought occurred to many that Rahm represented a rapidly encroaching era of selfishness and a turning point away from the examples of great players of the past.

That image, with all the contradictions and consequences of his decision, weighed on Rahm, who lost his unshakable veneer when he began playing in LIV events early this year. It was a change reminiscent of when he first appeared in public after shaking up the world with his own stunning—and personally devastating—defection to LIV.

Right away, Rahm made comments that seemed nostalgic for the PGA Tour. In March he lamented that his automatic PGA Tour suspension for joining LIV would not allow him to defend three tournaments that he had won during his domination of the PGA Tour in early 2023—the Sentry at Kapalua, the American Express at PGA West and the Genesis at Riviera.

“Not being there was difficult,” he conceded sadly before recovering with the rote. “It’s a decision I made, and I’m comfortable with it.” But it was not comfortable enough to keep from longingly adding, “but I hope I can come back.”

In an interview with the BBC in April, Rahm unbiddenly lobbied his new LIV bosses to change the league’s format of 54 holes to 72. “The closer we can get LIV to do some of these things, the better,” Rahm said.

Most of Rahm’s 2024 golf lacked fire. Against LIV fields with a lack of depth, he played indifferently, notching two third-place finishes but staying winless in his first 10 events. He was worse in the majors, finishing T-45 at the Masters, missing the cut at the PGA Championship and . Something was clearly off.

“He’s not on the cutting edge the way he was,” said commentator and former European Ryder Cup captain Paul McGinley on the eve of the Open Championship at Troon. “His performances in majors are showing that. I don’t think he’s in a happy place; he doesn’t look content on the golf course.”

MORE: From near gold to missing a medal, Jon Rahm’s late stumble at the Olympics ‘stings’

ONE VETERAN TOUR INSIDER I SPOKE WITH IS certain that Rahm is experiencing deep regret. “I am 100 percent positive that if Jon could give the money back to the Saudis and come back to the tour, he couldn’t write the check fast enough,” he says. “Now there are only four times a year when he’s playing that anybody is remotely interested. He thought his stature in the game was secure no matter where he was playing, and it was a bad miscalculation.”

Indeed, Rahm was set up for greatness on the PGA Tour, having hit the time-honored markers of a superstar in the making. He had fame, the respect of his peers, the admiration of the golf world and more than $70 million in career earnings from the PGA Tour and DP World Tour. At 28, he had won the 2023 Masters and the 2021 U.S. Open and had 11 PGA Tour wins to go with eight on the DP World Tour. He had been World No. 1 for 52 weeks. His big game and superb touch were accompanied by a love for competition fueled in part by appreciation for golf history and where he could fit into it.

Rahm said his perspective on entreaties from LIV changed after June 6, 2023, when the PGA Tour signaled it would be willing to work with the Saudi's Public Investment Fund on a “framework agreement.” “That opened the door for me to do the same thing,” he told the BBC in April. Once he reconsidered the realities, historical greatness took a backseat to “a duty to set my family up as best as possible,” Rahm said, and “I’m getting paid more to play the same sport and have more time. I don’t know about most people, but that sounds great to me.”

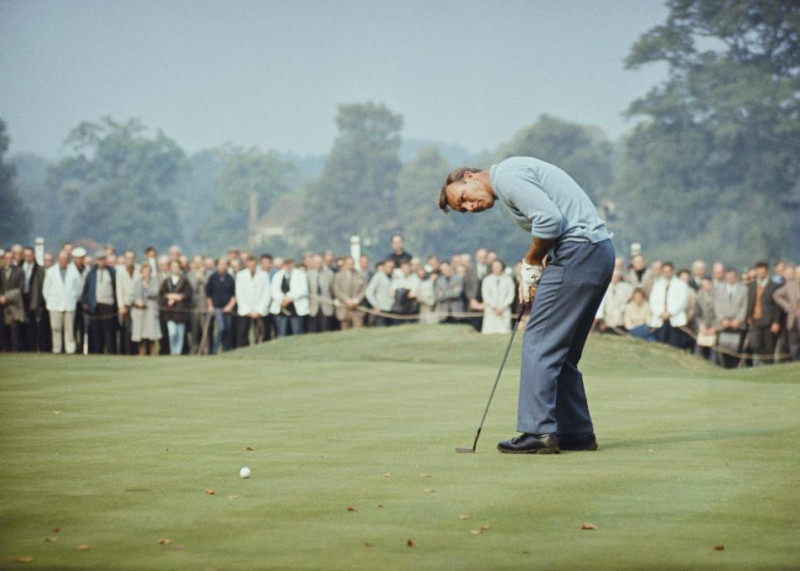

KING REIGNS Arnold Palmer won seven majors from 1958 through 1964.

Don Morley

Once he left, Rahm came to see his move as a step toward unification. “I could be the start of a tipping point,” he said. Such comments were not popular with his former colleagues at the PGA Tour. According to the anonymous “Undercover Pro” interviewed by Golf Digest senior writer Joel Beall, because they believe his defection, coming when PIF and the PGA Tour had agreed to cease recruiting during negotiations, widened the schism and prolonged the path to a solution. The players had been unified in staying put on the PGA Tour while a deal was being worked out, and Rahm had hurt that cause.

When Rahm said at his press conference at the PGA Championship in May that he still sees himself as a PGA Tour member despite his suspension for going to LIV, and that he would play in PGA Tour events if allowed, it drew a strong on-air reaction from former player and Golf Channel commentator Arron Oberholser, who said, “I wanted to wring his neck through the television screen … and every player in that locker room, if they watched that, should be incensed.”

Whether they are, Rahm’s actions, more than any earlier LIV signing (including those of major-championship winners Mickelson, Bryson DeChambeau, Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka, Cameron Smith and Patrick Reed) brought further clarity to some hard truths.

MORE: What tour pros really think about Jon Rahm

The idea that the best PGA Tour players can be counted on to put the existential health of the tour above their new potential fortunes is over, as is the surety that an elite player in his prime will put a single-minded pursuit of greatness ahead of the new money.

Why does that matter? Because the most interesting parts of golf history are written through the stories of its best players. When they are at their best, the game is at its best. The striving for glory and greatness is the best producer of epic golf. Bobby Jones’ Grand Slam, Byron Nelson’s 11 victories in a row, Ben Hogan’s six major-championship triumphs after a near-fatal car accident, Arnold Palmer’s charismatic years of dominance and Jack Nicklaus’ unprecedented two decades at the top have all been repositories and beacons of what golf greatness entails. With the “irrational” financial offers that have destabilized professional golf, LIV has lessened the long-presumed importance of week-to-week tournament play, and drained the sport of some of the passion and intensity that is essential to this otherwise slow-moving game.

THE MAVERICK Bryson DeChambeau has rebutted the idea that a soft schedule sates a hunger to be great.

Alex Slitz

LIV has discovered this. Despite its novel peripheral efforts for attention, the casualness in LIV’s presentation fails to project energy and remains antithetical to serious competition. To a lesser degree, the now defunct, lucrative and no-cut WGC events on the PGA Tour also suffered from low intensity and were often dismissed as “cash grabs.”

Comedian Jerry Seinfeld could have been cautioning pro golf when he recently wondered, on the “Blocks Podcast” in May, “What the hell happened that money became everything? In the 1970s, it was, ‘How cool is your job? How cool is what you’re doing? If your job’s cooler than mine, you beat me.’ … If your work is unfulfilling, the money will be, too.”

Nobody could accuse Gary Player of being unfulfilled in his work. The nine-time major winner, whose autobiography is titled, To Be the Best, always acted like he had the coolest job in the world. At 88, he remains driven, still shooting even par rounds from the middle tees, still seeking challenge.

“You can’t make money your objective and be a superstar, which to me is someone who wins six majors or more, though I wonder who is going to get there anymore,” Player says. “You must want something deeper. I made myself love adversity because you can’t escape it. I was that crazy to be a champion, but that sort of attitude is much harder to sustain now because the game is wrapped around money like never before.”

THE SURETY THAT AN ELITE PGA TOUR PLAYER IN HIS PRIME WILL PUT THE SINGLE-MINDED PURSUIT OF GREATNESS AHEAD OF NEW MONEY IS OVER.

Nick Faldo, who made Player’s exclusive designation with his six majors, says money can be an indirect motivator when it’s needed, an impediment when it no longer is.

“When I was in my early prime playing against guys like Seve and Greg, I knew I had to win to change my lifestyle—get a good car, fly first class, a house near Wentworth,” Faldo says. “I just tried very hard to win, knowing the money would come with that effort, but it’s harder to be great if you don’t need to win, and as much as I played to test myself against the best, that became a challenge for me as I got older. These young guys now are suddenly getting enormous major sport money and have everything they want; I don’t think they will push themselves as hard as we did.”

Even Jack Nicklaus, who sustained greatness longer than anyone in history and who enjoys his role as a sounding board for many of today’s young stars, confesses some concern that the new money could have a dulling effect on competition. “I would think that it’s only human nature that it would affect motivation and performance. It’s what I worry about on the tour.”

STAYING POWER Jack Nicklaus won 18 professional majors from 1962 to 1986.

Focus On Sport

Other factors may also be softening the competitive edge. The new emphasis on improving mental health among elite athletes has touched golf, especially with the suicide death of Grayson Murray in May. The PGA Tour has acknowledged that it is providing counseling to address new stressors like the social-media news cycle, and Dr. Michael Lardon is advocating for a mental-health trailer along the model of the tour’s successful fitness trailer that started in 1985.

Rory McIlroy emphasized enjoyment when he returned to the game at the Scottish Open a month after his painful loss at the U.S. Open at Pinehurst, speaking of a revitalizing sojourn he spent in New York City as part of a new approach. “I need to take a step back and appreciate what I’ve done in my career and in my life and enjoy my success,” he said. “I don’t really enjoy my success, and I haven’t, I would say, for the last five years. I’m committed to having more fun going forward.”

MORE: The confusing case of Rory McIlroy's golf swing, explained

Asked about some differences among today’s young players compared to previous generations, sports psychologist Gio Valiante cited a 1983 quote from the maniacally driven Hogan, who grew up poor and at age 9 witnessed his father’s suicide. “I feel sorry for rich kids now, I really do,” Hogan said, “because they’re never going to have the opportunity I had. Because I knew tough things. I had a tough day all of my life, and I can handle tough things. They can’t.” Says Valiante: “I suspect a far greater majority of today’s players come from more nurturing backgrounds, which tends to breed less obsession with greatness. The problem with being well adjusted and still trying to be great is that at some point, the question occurs, ‘What the hell am I doing this for?’ If the answer isn’t clear, that journey will end.”

SINGULAR DRIVE Ben Hogan won six of his nine majors after a near-fatal car crash.

Bettmann

PGA Tour observers have also noticed an increased degree of conviviality among players, whether because they are more conscious of the shared stresses of competitive tour life or simply because they are more comfortable. “Everyone is friendly now,” says a veteran caddie. “Probably much better and healthier for your life but for greatness in sport? Tiger used to be aloof. It wasn’t personal disdain, but he wanted to prove he was superior and almost took offense at the possibility someone thought they could beat him. It was part of his edge.”

Perhaps Tiger set the standard of greatness so high that it has drained the belief that it can be approached, let alone equaled. Only the iconoclastic Koepka, with five majors, is open about his belief. As he said in 2021, “In my mind, I’m going to catch him on majors.”

Deane Beman, the commissioner of the PGA Tour from 1974 to 1994, remains a visionary at age 86. Ironically, the man who in 1980 developed the Senior Tour in part to lengthen the moneymaking years of his members believes careers on the PGA Tour will be getting shorter and not just because of more money.

Beman lays out this sequence of reasons: Players are getting better younger. The latest example is Nick Dunlap, 20, who became the first player in history to win on the PGA Tour as an amateur and professional in the same year. Part of this precociousness comes from the less complicated power game that more forgiving equipment and faster swing speeds facilitate. Because the natural dissipation of youthful speed will become a greater competitive disadvantage, players will age out sooner. The shorter careers will result in fewer players compiling historically great numbers.

“It will be more difficult to become a superstar,” Beman says. “There will be fewer players considered in that category, they won’t win as much as their predecessors, and they won’t be around as long—more good golf but less greatness.”

ASCENDING Scottie Scheffler seems to have the inner fire and confidence to become great.

Michael Reaves

Of course, a few rare players will have the talent and internal wiring to separate them from the pack, no matter how much the world changes. Currently owning the stage is the alliterative duo of Scheffler and Schauffele, the duo in a race to be chosen PGA Tour Player of the Year.

Both are intelligent, gracious, low key and conspicuously non-materialistic. Both possess a blazing inner fire and confidence for golf. Scheffler, who recently passed Faldo for fifth place in career weeks at World No. 1, in the past two years has compiled ball-striking statistics exceeding even the best of Woods. At 28, he has won two of the past three Masters but seems equally well suited to capturing the other three majors with a temperamental putter seemingly his only hurdle. In 2021 he tried to explain to Golf Digest Senior Writer Matthew Rudy, his face no doubt fixed with the cheerful smile that undermines his case even as his achievements support it, that he has got a little something extra going on. “It doesn’t matter where I’m playing, I’m just an amped-up person. I can play this game.”

As for Schauffele, his two major victories this year on the back of several high finishes in past majors have given the 30-year-old and his well-rounded game the consensus inside track to complete the career Grand Slam ahead of the players who have each held three legs for several years—Spieth, McIlroy and Mickelson.

Chris Como, who has taken over the coaching reigns from Schauffele’s father, Stefan, says Xander is immersed in expanding a journey dedicated to finding out how good he can get. “He knows he has this aptitude for golf,” Como says, “and it’s become his fulfillment and his art, and it’s beautiful.”

WITH THE ‘IRRATIONAL’ FINANCIAL OFFERS THAT HAVE DESTABILIZED PRO GOLF, LIV HAS DRAINED THE SPORT OF SOME OF ITS PASSION AND INTENSITY.

Another duo, quite different, is Koepka and DeChambeau. Although most of the top players who have gone to LIV have seen their performances in majors decline, Koepka and DeChambeau, each with a win and a runner-up in major championships since going to LIV, have provided loud rebuttals to the narrative that a soft schedule and easy money sates the hunger to be great.

Koepka went to LIV because of the uncertain status of a knee injury that threatened to end his career. The knee improved, but just as he did on the regular events on the PGA Tour, Koepka doesn’t seem particularly motivated by regular LIV events, although he has won four of them in three years. Regardless of what league he plays for, Koepka, 34, cares about majors, believing he has the game and the mentality to prevail when conditions are toughest. However, this year, his best finish in a major was T-26 at both the PGA Championship and the U.S. Open, lending grist to the argument that LIV Golf’s environment is not ideal preparation.

DeChambeau, 30, would beg to differ. A maverick by nature, the shorter LIV schedule lets him indulge his obsession with total autonomy, leaving plenty of time for hitting the practice range for monster sessions or developing a successful YouTube channel that is focused equally on golf instruction and presenting a more likable version of himself. DeChambeau said that the team aspect of LIV has been good for him in contrast to the loner he was on the PGA Tour. To go with his U.S. Open win at Pinehurst, DeChambeau was T-6 at the Masters and second at the PGA Championship before missing the cut at Troon, after which he vowed to bring more shot variety, a departure from the way he likes to play, to the next Open. In his own way, alternating between seeking attention and disappearing with his launch monitor, DeChambeau pursues greatness.

Where does Rahm fit in? The second half of the year got better when he tied for seventh at the Open. His last-round 68 started with three birdies that put him within range of the leaders, but he flattened out to play even par the rest of the way.

One week later he got his first LIV victory in England, his tearful reaction no doubt a release after months of stress as a lightning rod. He came to the Paris Olympics eager to win gold for Spain, but also determined to show, on the big stage, that he was still a force whose fire had not been doused.

And he was well on his way to doing so. Tied for the lead with Schauffele entering the final round, Rahm turned in four under 31 and then birdied the 10th hole to take a four-stroke lead. But Rahm played the last eight holes five over par, not only losing the gold medal to the PGA Tour-tempered Scheffler, who made up 10 strokes on Rahm on the final nine, but failing to medal at all.

"I’m assuming there’s gonna be motivation for the future. But right now, it’s more painful than anything else." —Jon Rahm at the Paris Olympics

Brendan Moran

It can be debated whether his inability to close should be attributed to decline in mental toughness or if he took on too heavy a psychic load. But there was no doubt that the ordeal left Rahm crushed. “I don’t remember the last time I played a tournament and felt this,” he said. “I think by losing today, I’m getting a much deeper appreciation of what this tournament means to me than if I had won a medal, right? I’m getting a taste of how much it really mattered ... I’m assuming there’s gonna be motivation for the future. But right now, it’s more painful than anything else.”

Rahm’s passion and pain was a reminder of the soulful player the PGA Tour has lost. Because even more than proving that playing for LIV has not diminished his fire, Rahm wanted that gold medal for the glory and greatness he’s always sought. As it stands, in 2025, he’ll have five more opportunities to resume that chase—the four majors and the Ryder Cup. But only five.

It’s possible that Rahm will be spending several prime years as a member of LIV, a dreaded “what if” in his career retrospective. If so, he can recalibrate and win tournaments unlikely to be significant on his record, wait for the majors to make history, and, as he did in signing with LIV, make family his top priority. His wife Kelley is due to give birth to their third child later this year.

This is pro golf’s lucrative limbo, a balance of competition and contentment, more smart plays to be made but not as much greatness.

More From Golf Digest+

How many shots can a tour caddie save you?

How many shots can a tour caddie save you?

How a Hall-of-Famer used this two-word swing mantra to perfect his tempo

How a Hall-of-Famer used this two-word swing mantra to perfect his tempo

The bizarre twist of fate that gave this pro full PGA Tour status

The bizarre twist of fate that gave this pro full PGA Tour status